Wait, We're The Oppressed Ones?, Part Two

How Grievance Politics Turns Religious Freedom Into a Weapon

If you read my last blog, Wait, We’re the Oppressed Ones?, you know I spent some time unpacking the very real feelings of persecution many white evangelical Christians experience—and how, more often than not, that sense of grievance gets weaponized for political gain.

At the time, I didn’t set out to write a series on the subject. Honestly, I figured one deep dive into the persecution narrative was enough.

But then April 22 happened—and, well, they kind of made the case for a part two for me.

On that single day, two very different versions of “religious liberty” played out on the national stage.

First, over at the Supreme Court, justices heard oral arguments in Mahmoud v. Taylor, a case asking whether public schools violate parents’ religious rights when they compel young children to receive instruction on gender and sexuality—without parental notice or the option to opt out. The petitioners, it’s worth noting, weren’t just evangelical Christians; they came from a range of religious backgrounds.

Meanwhile, across town, an entirely different “religious liberty” fight was unfolding: the first hearing of the Task Force to Eradicate Anti-Christian Bias in the federal government—the flagship effort born out of the Anti-Christian Bias Executive Order Trump signed just weeks after returning to office.

I hadn’t planned on writing a follow-up so soon. But this hearing was almost too perfect an example of how the persecution narrative I wrote about gets manufactured and deployed in real time.

So here we are: Part Two. And yes—I know my last piece was long. This one’s no different. But I hope you’ll stick with me to the end, because if we’re going to talk about persecution, we at least owe it to ourselves to understand what’s actually going on.

The Strange Optics of the Task Force Launch

The Task Force meeting kicked off with opening remarks from Attorney General Pam Bondi, surrounded by several members of Trump’s cabinet (you can find the full list of attendees here).

At first glance, Bondi leading this charge might seem odd. Why would the head of the Department of Justice be spearheading a conversation about religious bias?

Well, for starters, many religious discrimination cases do fall under civil rights law—so symbolically, the DOJ weighing in makes sense. But Bondi’s role here wasn’t just about symbolism. It was, in many ways, the culmination of years of work she’s done alongside Religious Right leaders and advocacy groups—work that has uniquely positioned her to not only lead this Task Force but to help shape the narrative it promotes.

During the hearing, she framed the conversation around “peaceful Christian Americans who were unfairly targeted by the Biden Administration for their religious beliefs.” That framing isn’t accidental. It’s the same grievance-centered language that has been carefully cultivated by many of the groups Bondi has worked with over the years.

Bondi, Bias, and the Religious Right: A Long History Together

To really understand what’s happening here, we need to talk about Pam Bondi—not just as an attorney general, but as a figure deeply connected to movements that advocate for a stronger blending of religious identity and public power.

Bondi made history as the first woman elected as Florida’s attorney general. After that, she joined Trump’s legal team during his impeachment hearings and eventually landed the role of U.S. Attorney General. But along the way, Bondi has consistently aligned herself with Religious Right leaders and causes, often backing efforts to infuse religious values directly into public policy.

One telling example: she co-authored an op-ed with Paula White-Cain—Trump’s spiritual advisor and head of the White House Faith Office—defending the high school football coach at the center of Kennedy v. Bremerton, the Supreme Court case about public prayer at school-sponsored events. (If you’re interested, we covered that case in detail on the podcast. [Watch here.])

But Bondi’s associations don’t stop there.

After her tenure in Florida, Bondi joined the America First Policy Institute (AFPI), a Trump-aligned think tank that has worked closely with dominionist figures like Lance Wallnau—a leader in the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR) movement. Wallnau is perhaps best known for championing the “Seven Mountains” mandate, the idea that Christians are called to dominate key sectors of society like government, education, and media. For more information about the Seven Mountains mandate or the NAR check out the interviews we’ve done with several experts on this topic, to include religious scholar Matthew Taylor, PhD. and theological professor André Gagné, PhD.

Bondi’s participation in AFPI initiatives like the “Courage Tour” alongside Wallnau underscores her continued alignment with these movements. Wallnau has even publicly praised Bondi, pointing to their shared mission of integrating faith-based ideology into national politics.

In other words: Bondi isn’t just showing up to this Task Force as a neutral government official concerned about religious liberty. She’s bringing years of ideological commitments and political relationships with her—and that context matters.

How the Persecution Narrative Gets Built

This brings us to one of the most important questions we should be asking:

Why did AG Bondi choose these examples? Why now?

When Bondi opened the Task Force hearing, the examples she cited weren’t random. They were carefully chosen touchpoints from a well-worn playbook of grievance politics:

Vandalism against churches.

Transgender visibility “co-opting” Easter.

Pro-life activists arrested.

FBI “spying” on Catholics.

If these sound familiar, that’s the point. You’ve probably heard some version of these stories on Fox News, in conservative religious media, or passed around on social media. They’ve been packaged into easily digestible headlines, stripped of nuance, and repeated often enough that they start to feel like undeniable proof that Christians are under attack.

And here’s the thing: the power of these stories isn’t in their accuracy—it’s in their repetition.

When disconnected events get stacked together and retold over and over as evidence of a larger conspiracy against Christians, they create the emotional weight needed to justify government action. It doesn’t matter if the events have different causes—or if some are outright mischaracterizations. The emotional pull is the point.

It’s the same psychological effect that makes you feel nervous about flying even when you know statistically it’s safer than driving. Familiar stories feel true. Fear reinforces belief. And that belief becomes the fuel for policy.

The result? What may have started as isolated incidents or culture war flare-ups gets elevated into a national crisis—and, in this case, into federal policy.

Claim #1: “Vandalism against churches was eight times higher in 2023 than in 2018.”

One of the headline stats Pam Bondi highlighted at the hearing was that vandalism against churches was “eight times higher in 2023 than it was in 2018.”

The number likely came from a report by the Family Research Council (FRC), which documented 915 acts of what they call “hostility against churches” between 2018 and 2023. Of those, 436 happened in 2023 alone.

And look, the FRC isn’t making up these incidents. Their methodology involved pulling from news reports, police records, and other open-source documents—cataloging things like vandalism, arson, bomb threats, gun-related events, and other forms of disruption at churches across the country.

But here’s where the story gets a lot more complicated than the soundbite suggests.

The types of attacks in that report aren’t all the same—and they aren’t all motivated by anti-Christian hatred. In fact, when you start to unpack the details, the motives range widely:

Some attacks clearly involve religious animus—like crosses desecrated, saints’ statues beheaded, or satanic graffiti sprayed across church property.

Others reflect political tensions, like pro-life signs defaced during abortion campaigns or pride flags ripped down during Pride Month.

Still others are racially motivated—especially attacks on historically Black churches, which have long been targets of white supremacist violence.

Take the example of a church in El Paso, Texas, where vandals spray-painted “666” and turned crosses upside down. That’s very different from the racially charged attacks where swastikas or KKK symbols are scrawled across Black congregations’ buildings.

When you bundle all these acts together under the umbrella of “anti-Christian bias,” you flatten a complex reality into one convenient story: Christians under siege.

It’s also worth noting that the FRC’s report doesn’t offer any comparative baseline—meaning we don’t know whether other houses of worship, like synagogues or mosques, experienced similar or even higher rates of attacks during the same period. Without that context, it becomes easy to frame these numbers as unique evidence of anti-Christian hostility, even when the data doesn’t fully support that conclusion.

And here’s something else that often goes unspoken but deserves to be said out loud: when we hear political leaders or advocacy groups talking about “anti-Christian bias,” they’re almost always talking about white evangelicals—whether they say it directly or not.

This was a key point I unpacked in my last blog, where survey data showed that white evangelicals are consistently the group most likely to feel that Christians are persecuted in the U.S. The perception isn’t shared to the same degree across other Christian traditions like Black Protestants, Catholics, or mainline denominations.

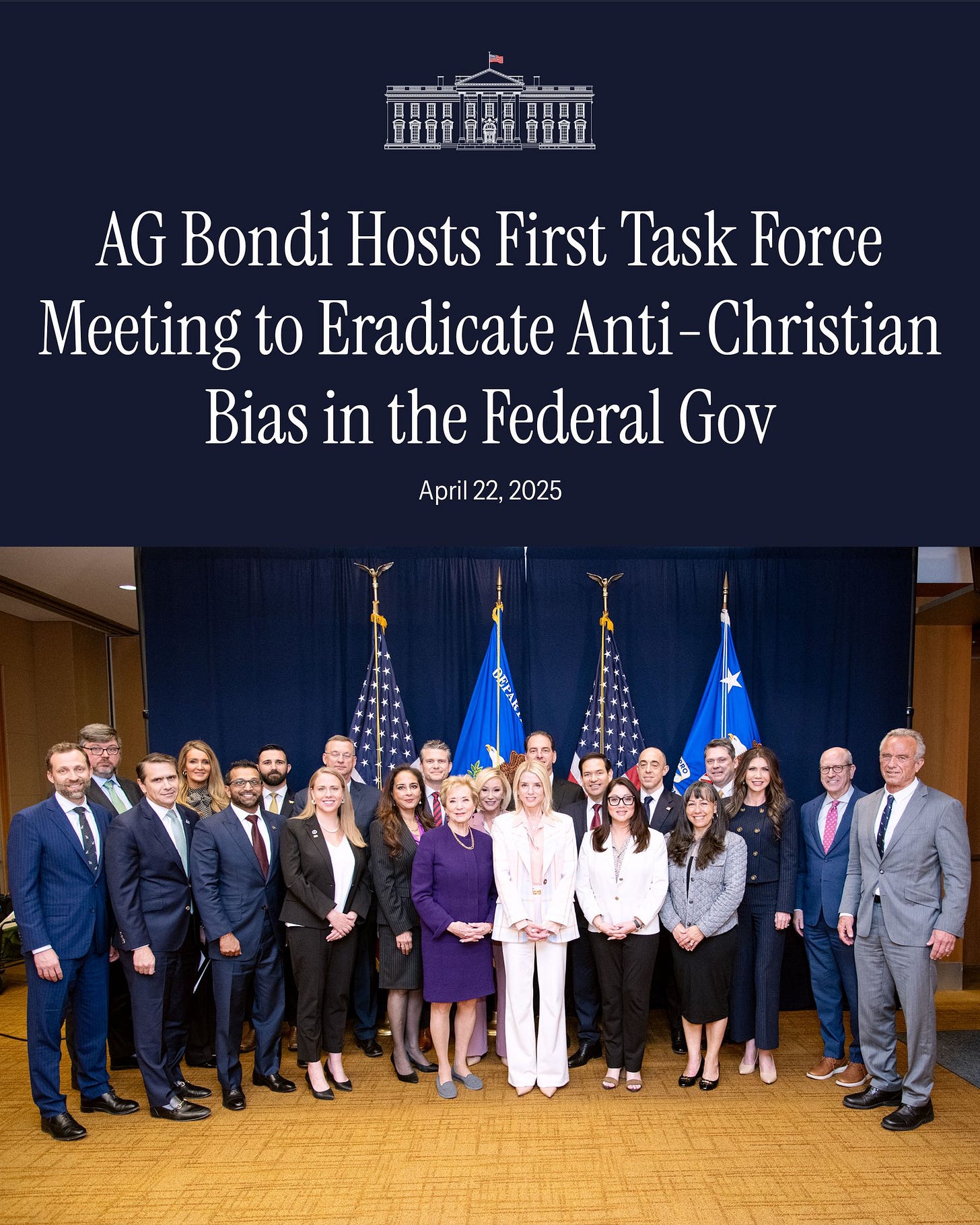

Once you recognize this pattern, it gets hard to unsee. Just take a look at the photo from the Task Force hearing itself—it’s a pretty clear snapshot of who this narrative is being built for.

And if your first instinct is, “Well, hey, FBI Director Kash Patel isn’t white,” you’re kind of proving my point. This isn’t about whether every single person in the room fits the same demographic profile—it’s about whose cultural grievances are being centered and elevated in the conversation.

What the FBI’s Hate Crime Data Actually Shows

Since Bondi is leading the DOJ—the same department that oversees the FBI—it’s worth asking: what do the government’s own numbers say about hate crimes in America?

According to the FBI’s official hate crime statistics, Jews remain the most targeted group when it comes to religiously motivated hate crimes—by a significant margin. In 2023 alone, nearly 70% of all reported religion-based hate crimes were anti-Jewish. Anti-Christian incidents (including Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox, and other denominations combined) accounted for a much smaller slice of the total.

To put this in perspective:

Annual anti-Jewish hate crimes consistently range between 800–1,800 incidents per year.

Anti-Christian hate crimes typically hover in the low hundreds—far below that figure.

The only recent spike in Christian-related bias cases wasn’t in violent hate crimes—it was in workplace religious discrimination complaints, particularly during the COVID vaccine mandate era, when there was a wave of religious exemption requests. (I briefly talked about why this happened in my previous blog)

But here’s the key point: if anti-Christian bias is as pervasive and widespread as the Task Force suggests, why doesn’t it show up in the government’s own hate crime data?

The selective use of the FRC’s church attack numbers—without this broader context—allows the persecution narrative to take center stage, even when the larger body of evidence tells a much different story.

The Role of Race in Church Attacks: Why Motive Matters

There’s another important layer here that rarely makes it into these conversations: how racially motivated violence against churches gets classified.

According to the FBI’s Hate Crime Data Collection Guidelines and Training Manual attacks are based on the primary bias motivation of the offender. So, if someone attacks a historically Black church and leaves behind racial slurs, swastikas, or KKK symbols, that incident is classified under “race/ethnicity/ancestry” bias—not “religion.”

This is why it’s so important to pay attention not just to the numbers, but to how these incidents are categorized, understood, and discussed.

When we talk about attacks on churches, it’s easy—and frankly, tempting—for some to lump every violent act or vandalism incident into the bucket of “anti-Christian persecution.” But if we care about truth, we need to look more closely at what’s actually motivating these attacks.

Consider the devastating 2015 shooting at Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston. Nine Black congregants were murdered by Dylann Roof, a self-described white supremacist. Roof didn’t target just any church because it was Christian—he specifically chose a historically Black congregation because of their race. His stated goal was to start a “race war.”

That attack, rightly, was classified as a racially motivated hate crime, not an act of anti-Christian bias. The location mattered, yes—but the motive mattered more.

This is the kind of nuance that often gets lost when we talk about bias or persecution in broad strokes. When church attacks are tallied up without attention to motive—when a racial hate crime, an act of political extremism, and a vandal spray-painting “666” on a wall all get tossed together under “Christian persecution”—we risk missing the real story.

We also risk something worse: erasing the specific histories of those most often targeted by violence. Attacks against Black churches have long been part of a brutal pattern of racial terror in this country. To flatten that reality into a generic claim of “religious grievance” doesn’t just blur the facts—it dishonors the true nature of the harm done. So when we hear claims about rising anti-Christian hostility, the right question isn’t just how many attacks? but also why?and against whom?

Because without that context, the numbers alone can tell a misleading story—one that too easily serves political narratives rather than the truth.

Claim #2: “Pro-Life Christians Are Being Arrested Just for Peacefully Praying”

Next on Bondi’s list of attacks on Christians: the claim that pro-life activists are being unfairly targeted and arrested simply for “peacefully praying outside abortion clinics.” If that were true, it would be a serious violation of both free speech and religious liberty.

But that’s not what happened.

The arrests in question were convictions under the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances (FACE) Act, a law passed back in 1994 after years of clinic blockades, harassment, and violence—including bombings and murders of abortion providers. The FACE Act makes it illegal to use force, threats, or physical obstruction to block people from accessing reproductive health services. A law that is at risk of being repealed.

This wasn’t about silencing peaceful protests. It was about stopping dangerous, aggressive tactics that put patients and providers at risk.

Consider this example: in one high-profile case, a group of activists chained themselves together to block the doors of a D.C. abortion clinic. In another, Matthew Connolly illegally barricaded himself inside a secure patient area at a Philadelphia Planned Parenthood, refusing to leave until SWAT officers physically removed him.

Calling this “persecution for prayer” might make for an effective soundbite—but it completely ignores the legal realities.

And here’s the irony: the same DOJ Bondi now leads? They dropped many of these cases after Trump returned to office, and in other cases were offered pardons. It’s hard to argue that these activists are being persecuted by the government when the government is actively letting them off the hook.

Persecution, by definition, requires the threat to be ongoing. Not retroactive.

Claim #3: “The FBI Spied on Catholics in Their Parishes”

Another claim repeated at the hearing—and a favorite in certain media circles—is that the FBI “spied on traditional Catholics in their churches.”

It’s a statement designed to provoke outrage, and to be fair, there is a kernel of truth at the center of this story. But like so many of these claims, the way it’s being presented is far removed from what actually happened.

The controversy centers on a leaked internal memo from the FBI’s Richmond field office, written in early 2023. The memo flagged concerns about a small subset of what it called “radical-traditionalist Catholic (RTC)” groups—fringe sects known to promote violent, far-right ideologies cloaked in religious language. The memo specifically distinguished these groups from mainstream Catholic congregations.

It also suggested that the FBI consider developing sources within these extremist circles, given their overlap with domestic terrorism threats.

Now, was this memo a bad idea? Absolutely. The FBI itself quickly acknowledged as much. After the memo leaked and sparked backlash—including from Catholic leaders and members of Congress—the agency rescinded the memo, disavowed the approach, and then FBI Director Christopher Wray called it “deeply flawed.”

Wray also made clear that the memo had been drafted by a single analyst at one field office and was not reflective of national policy. There was no widespread campaign to infiltrate Catholic parishes across America.

But in the hands of persecution narrative architects, that important context gets stripped away. Instead, the story becomes: The Biden FBI is spying on Catholics simply for being Catholic.

That version of the story ignores both the corrective actions taken and the specific concerns about extremist violence. More importantly, it takes a legitimate debate—how to balance counterterrorism work with religious freedom—and flattens it into a simplistic, weaponized talking point.

Claim #4: “Biden Declared Easter Sunday to Be Transgender Day of Visibility”

And then there’s the Easter controversy—the claim that President Biden “declared Easter Sunday to be Transgender Day of Visibility.”

At the hearing, this was framed as one of the most blatant examples of the government’s supposed hostility toward Christians, presented as if Biden intentionally set out to co-opt the holiest day in the Christian calendar in favor of a progressive social cause.

But here’s what actually happened.

Transgender Day of Visibility (TDOV) has been observed every year on March 31st since 2009—long before Biden was president. In 2024, March 31st happened to fall on Easter Sunday. This overlap wasn’t the result of any policy decision or cultural attack—it was a coincidence of the lunar calendar, which determines the date of Easter each year.

Biden’s administration issued the same annual TDOV proclamation it has issued in previous years, consistent with past practice. No separate or additional statement was made tying TDOV specifically to Easter.

Calendar overlaps like this happen all the time. In 2002, Easter fell on César Chávez Day. In 2013, it also coincided with the International Transgender Day of Visibility, just as it did in 2024. In 2025, Easter fell on April 20—which is also Adolf Hitler’s birthday, a date often used by white supremacist groups for rallies.

Would anyone seriously argue that any president acknowledging Easter in 2025 is “honoring Hitler” because of that calendar overlap? Of course not. Because we understand that the date is set by ecclesiastical tradition, not political leaders.

But by selectively highlighting this overlap—and framing it as intentional—the Task Force discussion tapped into the same emotional reservoir that fuels so much of the persecution narrative: the idea that any cultural recognition of marginalized groups is an attack on Christian identity.

The fact that this claim was elevated at the launch of a government task force on religious bias speaks volumes about how grievance politics works. It doesn’t require evidence of actual persecution. It only requires a story that feels insulting enough to keep the outrage machine running.

What’s Really Going On Here: The Playbook of Manufactured Persecution

At this point, we’ve walked through the key claims raised at the Task Force hearing—and hopefully, it’s clear that the stories being told are often far messier, more complicated, and in many cases, flat-out misleading once you dig into the details.

But the thing is: none of this is new.

The tactic of amplifying isolated incidents to create a sense of widespread Christian persecution has been a core strategy of the Religious Right for decades. Journalist Sarah Posner sums up the approach perfectly in her book Unholy: Why White Evangelicals Worship at the Altar of Donald Trump:

“Amplify a single local flare-up into a national issue, emblematic of elite liberal orthodoxy run amuck.”

The formula is simple, effective, and devastating:

Identify a local incident—a school policy, a vandalized nativity scene, a clinic protest arrest.

Blow it up into a symbol of national crisis.

Frame it as evidence of a coordinated assault on traditional values.

The power of this strategy is that it doesn’t need a mountain of evidence—just a compelling story. The people pushing this narrative are banking on the fact that most folks won’t stop to dig any deeper. But if you’ve made it this far, you’re clearly not most folks. Every hyperlink in this blog is here for a reason—to help you follow the trail and see the bigger picture for yourself.

Because once a single bad incident gets pulled out of context and repeated enough times, it becomes something more than a story. It becomes proof—proof that confirms fears, stokes outrage, and rallies people to a cause. Whether or not it reflects reality becomes almost beside the point.

It’s the same playbook behind the annual “War on Christmas” outrage cycle. Each December, a handful of retailers opting for “Happy Holidays” instead of “Merry Christmas” becomes spun into a cultural indictment of the nation’s supposed abandonment of its Christian roots. Never mind that actual church attendance, not Starbucks cup designs, remains the more meaningful measure of faith’s role in society.

But these tactics aren’t just about cultural skirmishes. They’re about power.

When grievance becomes the lens through which people view the world, it fuels political engagement. It justifies government action. It creates urgency. And most of all, it builds loyalty—not necessarily to faith itself, but to the political leaders and advocacy groups claiming to be its defenders.

That’s the underlying function of the persecution narrative: it transforms cultural anxiety into political capital.

Why This Matters

Let me be clear: religious discrimination does exist. When it happens, it deserves to be called out and addressed. No one—whether Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, atheist, or otherwise—should face violence, harassment, or exclusion because of what they believe. Full stop.

But if we’re going to talk about religious liberty honestly, we have to be willing to tell the difference between real threats and manufactured outrage.

The danger of the persecution narrative isn’t just that it gets the facts wrong (though it often does). The real danger is that it cheapens the idea of persecution itself. It takes the language we should reserve for true injustice—genocide, state-sponsored repression, targeted violence—and applies it to things like Target selling rainbow pride merchandise or a clinic protester being held accountable for blocking a doorway.

Meanwhile, the actual stories of people whose religious freedom is under threat—minority faith groups, racialized religious communities, religious dissidents abroad—get pushed out of the spotlight.

And maybe that’s the point.

The persecution narrative doesn’t exist to amplify the vulnerable. It exists to consolidate power among those who already hold the mic.

Final Thoughts: Faith as a Political Weapon

If you’ve made it this far (and God bless you if you have), here’s what I hope you’ll take away:

The next time you hear a politician or media outlet warning about “attacks on Christianity,” ask yourself a few questions:

What’s the actual evidence?

Who is being centered in the story?

Whose suffering is being highlighted—and whose is being ignored?

Is the goal here to protect faith, or to politicize it?

Because protecting faith—real religious freedom—requires clarity. It requires honesty about where threats are coming from, who is affected, and what justice actually looks like. Weaponizing persecution language for political gain may score points in the short term. But in the long run, it undermines the very idea of liberty it claims to defend.

Thanks for sticking with me. If you haven’t read the first part of this series, Wait, We’re the Oppressed Ones?, I recommend going back and giving it a look—it helps set the stage for this conversation.

And as always, if someone from the Family Research Council wants to come on the podcast and talk about their report, my offer still stands. I’m more than happy to have the conversation.

Will, this is a powerful and cogent exploration of this faux crisis. I'm a devout Christian, and my observation--beyond the obvious power consolidation you write about here--is that the pushback from the culture isn't about Jesus (or Yahweh!) but about the hateful, small-minded beliefs and practices driving many away from faith. The same things manifested by this group trying to use government power to shore up their privilege, and their hateful beliefs. Thank you for this.