Wait, We're The Oppressed Ones?

How Christian Persecution Became a Political Identity — and a Powerful Commodity

Around 2010, I had the opportunity to visit Saudi Arabia for a couple of weeks. It’s a stunning country — rich in history and, well, just plain rich. To give you an idea, this was pre-DoorDash, but you could still get McDonald’s delivered to your door for about twenty-five cents. As someone with a very limited diet, that was a lifesaver.

At the time, I was a youth pastor — though I wasn’t there on a mission trip or doing any kind of evangelism; it was strictly work-related. Still, I couldn’t ignore the quiet tension that surrounded religion. For those who don’t know, the majority religion in Saudi Arabia is Islam, specifically Sunni Islam, and I identify as a Christian.

Warnings were everywhere: proselytizing was illegal, and blasphemy against Islam could, in theory, carry the death penalty. While no one had been executed for blasphemy since 1992, the threat of long prison sentences — or worse, an encounter with the once-feared religious police — felt very real. It was the first time in my life I ever felt truly vulnerable because of my faith. I wasn’t doing anything wrong, but I couldn’t shake the quiet fear that something as simple as being known as a Christian might get me in trouble.

Thankfully, I made it out unscathed and even built a few friendships along the way. But that experience stuck with me. It gave me a glimpse — however brief and mild — of what it feels like to be part of a religious minority, to walk through public spaces with that low hum of anxiety, wondering if who you are could be a problem. As a person of color in America, I was already familiar with what it feels like to be part of an ethnic minority — to navigate spaces where you’re not always sure if you’re being fully welcomed or quietly scrutinized. But this was different. This time, it wasn’t about how I looked — it was about what I believed. And that added a new layer of vulnerability I hadn’t experienced before.

Digging for Sand Roses, Searching for Perspective

But what I was feeling wasn’t just paranoia. Between 2010 and 2021, nearly 500 foreign nationals were executed in Saudi Arabia — about 39% of all executions in the country during that time. I don’t usually research execution rates before traveling, but in hindsight… maybe I should’ve. Especially since my local guide casually mentioned that a beheading had happened not long before my visit.

So when a few people I’d just met asked if I wanted to go find “sand roses” in the desert, I had a moment — a very real, very sobering moment — where I questioned whether I was walking into something I might not walk back from. I didn’t even know what a sand rose was, and we were heading off-grid with strangers, in a country where my religion could easily be seen as subversive or even criminal. Earlier that week, I had tried to prep a sermon I planned to give after returning home — something reflective about my time in Saudi Arabia. But every one of my go-to Bible websites was blocked. I couldn’t access the resources I normally relied on, because they were banned under government censorship. That quiet restriction hit me hard. Even my ability to privately study Scripture was being filtered, because physical bibles are illegal to own.

Anyways, I said yes to the sand rose adventure, because I love cultural experiences — but in that moment, I felt the vulnerability of being part of a minority faith in a place where religion wasn’t just a belief system, it was the law. That experience didn’t just rattle me — it reframed how I think about what it means to live in a country where religious tradition defines everything. It made me more aware of how powerfully religion can shape culture, law, and daily life — and how disorienting, even dangerous, it can feel when you’re outside that dominant framework.

About an hour into the trip, we’d left the city behind entirely. At some point we weren’t even on a road anymore — just driving across sand, passing the occasional camel farmer. Then we stopped. Middle of nowhere. No cell signal. My new friends pulled out some shovels and told me to start digging.

Let’s just say my brain was doing cartwheels trying to convince myself I wasn’t digging my own grave. The folding chairs should’ve been a clue that I was probably safe — or that I was dealing with especially patient murderers. (Spoiler: it was the former.)

Understanding the Persecution Narrative

That experience was the closest I’ve ever come to feeling persecuted for my faith. I wasn’t breaking any laws, but I couldn’t shake the fear that I might be outed as a Christian. It was surreal — especially the moment I found myself standing alone on a busy street during Salah prayers. I didn’t know the customs, the expectations, or the unspoken rules. All I knew was that I was clearly part of a minority religion. And that felt strange. Isolating, even.

It wasn’t the first time I’d been in a country where Christianity wasn’t the dominant faith. I had a similar experience when I deployed to Iraq, where Islam is also the majority religion. But that was different — I was with the U.S. military, and I was in the infantry. That kind of backing changes everything.

Even if your personal beliefs put you in the minority, being part of a strong, structured community gives you a sense of protection. Back then, I had that. I had a team. I had a mission. And let’s be honest — being heavily armed doesn’t hurt when it comes to feeling secure, especially when your faith feels unfamiliar in the surrounding culture.

There’s real comfort in knowing you’re not alone — that you’re connected to something bigger, something steady. That kind of belonging can quiet a lot of the anxiety that comes with feeling out of place.

Fast forward to today, and I’ve been thinking a lot about that feeling — that sense of being on edge, unsure if you belong, always aware that you’re somehow different, and looking for a larger group to anchor you. And no, I’m not talking about being a person of color who could lip-sync every Wilson Phillips song and spent weekends playing Magic: The Gathering (though yes, that too). I’m talking about the kind of unease that some American Christians now describe — a feeling of cultural displacement, even persecution. And while I don’t personally share that same fear in this season of my life, I get the desire to find something — or some group — that reminds you you’re not alone. Call it toxic empathy or maybe just curiosity, but I’ve been trying to sit with that. Because more and more Christians in the U.S. are saying they feel pushed to the margins.

How Persecution Became a Platform

This sentiment has become especially pronounced among one of President Trump’s most loyal voting blocs: white evangelical Christians. So much so that, in his first few weeks back in office, President Trump signed an Executive Order aimed at “Eradicating Anti-Christian Bias.” But this action by the President shouldn’t surprise us. Then candidate Donald Trump put it this way during his 2016 campaign kickoff speech at Liberty University:

And more recently on the 2024 National Faith Advisory Board call:

This Isn’t My Politics, But It Is Their Reality

Now this might surprise you, but our show isn’t exactly huge. So the fact that you’re even reading this far probably means you either like what we do — or you’re related to me. (Hi, Mom.) I bring that up because I don’t have enough data to know where my readers fall on the political spectrum. But given my own views, I’m guessing there aren’t a ton of hardcore Trump supporters here. And I’d love to change that.

Still, wherever you land politically, if you believe that perception shapes reality, then it’s crucial to understand that for many white evangelical Christians, this is their reality. They genuinely feel under siege. And when someone comes along promising to protect them — to defend their faith, their values, their way of life — that person is often granted wide latitude, even grace, to do and say things others would never get away with. I mean, I don’t think the now-pardoned 1,600 people who stormed the Capitol did so because they thought the election was fair. They acted on a perception — one that had been carefully shaped, reinforced, and sold to them as truth.

The point is, we shouldn’t dismiss anyone’s experience — especially when those feelings are being shaped, reinforced, and mobilized. We should ask questions, look at the data, and try to understand what’s driving the narrative. And when we do, we find a consistent trend: in survey after survey, white evangelicals report that they believe discrimination against Christians is more common than discrimination against gay and lesbian people, and as we will see later, this extends to other marginalized groups. (Source: AEI Survey Center on American Life)

It also shouldn’t be lost on anyone when this feeling of cultural displacement began to intensify. Hint: Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 Supreme Court decision that legalized same-sex marriage nationwide, marked a pivotal moment. Just one year later, the 2016 presidential election gave then-candidate Donald Trump the opportunity to channel that growing sense of loss into a political identity rooted in grievance and perceived persecution.

Since then, white evangelical support for Trump has remained remarkably strong: around 80% in 2016, 75–76% in 2020, and 82% in 2024, according to various exit polls and post-election analyses. This enduring loyalty suggests that the perception of cultural marginalization isn’t just personal—it’s become deeply political. American Enterprise Institute (AEI) senior fellow Daniel Cox gave one of the more insightful explanations for why this shift happened:

“There’s another reason white evangelicals have come to believe that they, rather than gay and lesbian people, experience discrimination—they are being told they are. Fears that conservative Christians are facing an increasingly hostile cultural climate are being fanned by political elites. Stoking the specter of persecution can pay large dividends. It keeps people tuned in and paying attention, providing a strong incentive to donate, vote, and volunteer. If an elected official can convince you that they are the only thing standing between you and oblivion, they do not have to do anything else to win your vote. Character flaws, sexual misbehavior, or financial misdeeds are easily overlooked.”

Cox and many other researchers tie this perception of persecution most strongly to white evangelical Christians. Now, it’s worth pausing here, because that phrase — white evangelical — can sometimes feel like a label that’s more accusatory than descriptive, especially if you identify with that group. So why do experts use it?

Understanding White Evangelical Identity in a Changing America

Simply put, when researchers, journalists, and scholars talk about "white evangelicals," they’re referring to a specific demographic group within American Christianity that consistently shows distinct patterns in political attitudes, cultural views, and religious behaviors. The term isn’t meant to stereotype individuals or flatten the diversity within that group — rather, it’s a way of understanding broader trends.

In this context, the perception of Christian persecution is deeply tied to identity — particularly white evangelical and conservative identity. One way to understand this is by looking at how conservative-leaning groups, especially Republicans, respond to questions about discrimination. According to PRRI, Republicans are more likely to say that white people (57%) and Christians (62%) face “a lot” of discrimination in the U.S. than they are to say the same about any racial or ethnic minority group — including Black people (52%), Hispanic people (45%), and Asian people (37%).

These patterns become even more pronounced among Republicans who trust Fox News as their primary news source. Among this group, only 27% say Asian people face a lot of discrimination, 34% say the same about Hispanic people, and 36% about Black people. By contrast, a majority (58%) believe white people are heavily discriminated against, and an overwhelming 73% believe the same about Christians.

This doesn’t mean that all Republicans — or all white evangelicals — are racist or uninterested in addressing inequality. But when large portions of these groups consistently perceive themselves as the most discriminated against, even more so than historically marginalized communities, it raises critical questions: Why is that? What cultural, theological, or media influences are shaping this perception? And perhaps most importantly, how does this worldview affect their engagement with broader conversations about race, equity, and justice?

And really, that’s why Faithful Politics exists in the first place— to help sort through questions like these with humility, nuance, and a bit of courage.

How Christians View the Role of Religion in Government

When exploring why some Christians — particularly white evangelicals — feel increasingly persecuted in America, it helps to understand how they view the role of religion in government. According to Pew Research Center, a majority of Americans (71%) believe that religion should be kept separate from government policy whereas only 28% think government policies should support religious values.

However, opinions shift significantly depending on political affiliation. Among Trump supporters, 56% favor keeping religion and policy separate, but a substantial 43% believe the government should support religious values. Among Biden supporters, that divide is far more stark: 86% want religion kept out of government policy, while only 13% support integration.

The differences become even more pronounced when looking at race and religion. For example, 61% of white evangelical Protestants who support Trump say government policies should support religious values, compared to just 39% of white non-evangelical Protestants and 39% of Catholics in the same political camp. Among Trump supporters with no religious affiliation, only 16% favor government support for religious values.

On the Democratic side, Black Protestants who support Biden are more likely than other Democratic religious groups to favor a closer connection between religion and policy — 35% say government should support religious values. In contrast, only 7% of white mainline Protestants and even fewer religiously unaffiliated Biden supporters share that view.

These data points help paint a more nuanced picture: the perception of Christian persecution is often shaped by not just religious identity, but also how people believe religion should (or shouldn’t) influence public life. That belief varies not only across political lines, but also by race, denomination, and media consumption — all of which add layers to the broader conversation about faith, power, and belonging in American society.

According to the Pew data, 61% of white evangelical Protestants who support Trump believe the government should actively promote religious values. This reflects more than just a theological conviction — it signals a political identity shaped by the belief that their faith is under siege. So when a figure like the President of the United States — someone many wouldn’t exactly describe as a “practicing” Christian — begins advocating for more religion in public life, it’s worth asking what kind of religion he’s promoting, and who it’s really meant to serve.

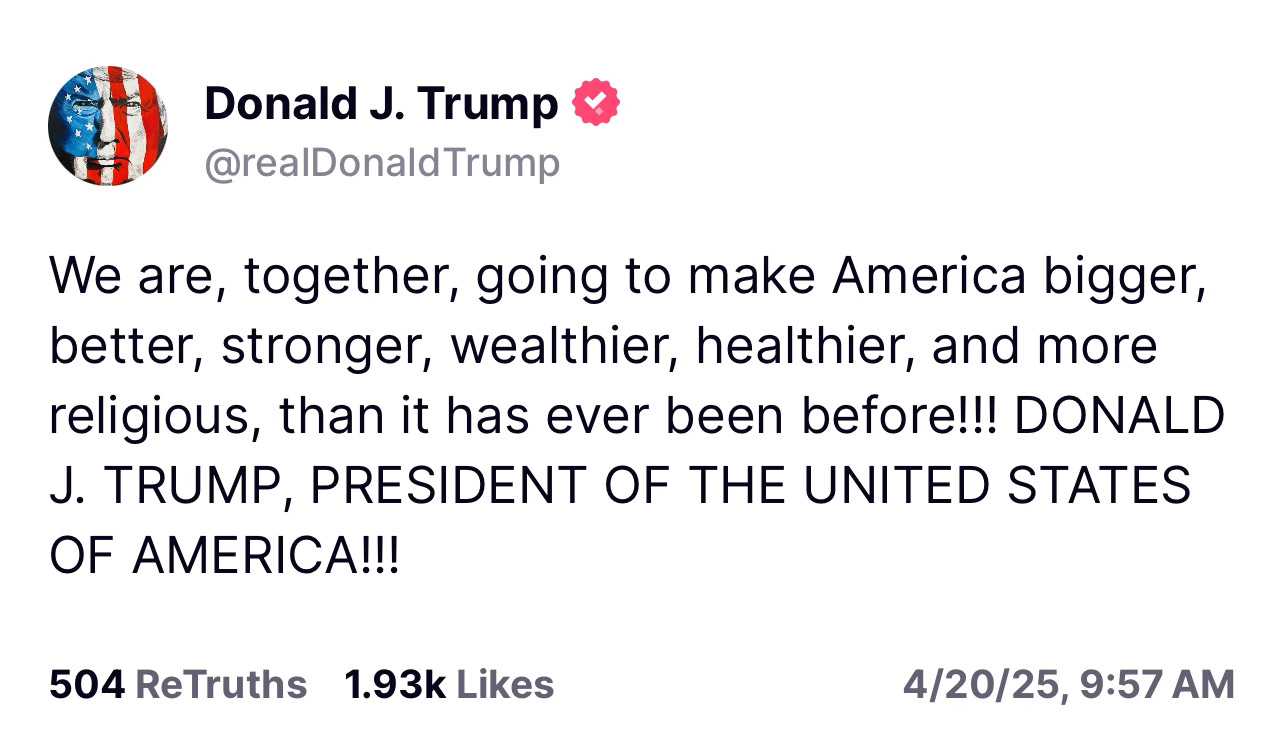

Donald Trump taps directly into the growing sense of religious persecution felt by many of his supporters. His promise to make America “more religious than it has ever been before” (on Easter of all days) isn’t just a nod to his perceived Christian bona fides — it’s a calculated signal. For many white evangelicals, this message speaks to a deeper longing: not just for spiritual renewal, but for the restoration of a cultural dominance they believe they’ve lost.

But here’s the challenge: restoring one’s religion shouldn’t require elevating a politician, especially one whose life and leadership often run counter to the teachings of Jesus. Religious freedom is already protected in the U.S. — Christians have vast networks, media platforms, and institutions. What’s changed isn’t their legal standing, but their cultural centrality. Losing influence in a pluralistic society is not persecution. It’s the natural result of others gaining the space they’ve long been denied.

Trump doesn’t just recognize that sense of loss — he amplifies it. He positions himself as both defender and redeemer, someone who promises power under the banner of protection. But in doing so, he risks turning religion into a political identity — one that demands loyalty not to the gospel, but to the candidate who claims to defend it.

When Cultural Loss Feels Like Persecution

That disparity isn’t just theological. It reflects a deeper and more emotional sense of cultural dislocation. Many white evangelicals aren’t only reacting to the loss of religious influence — they’re reacting to a loss of cultural primacy. In a country where evangelicalism was long tied to mainstream norms, any shift away from that centrality can feel like marginalization, even if it's actually part of a broader move toward inclusion.

This contrast in how Christians experience social change helps explain why the narratives of persecution and cultural displacement have merged so seamlessly — and why they’ve become so politically potent. As institutions, media, education, and corporations shift to become more inclusive and reflective of diverse experiences, some interpret these changes not as progress, but as erasure.

That’s why DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) efforts have become such a lightning rod in these circles. While many white evangelicals view DEI programs with deep suspicion — associating them with critical race theory, reverse discrimination, or even anti-Christian ideology — other Christian communities, particularly Black Christians, often see DEI as a long-overdue effort to confront generational injustice.

According to The Intercept, this division has created fertile ground for political leaders like Donald Trump to frame DEI not just as a flawed policy approach, but as part of a broader anti-Christian, anti-American agenda. And in that framing, many conservative Christians have remained silent — not necessarily because they oppose fairness or inclusion, but because they’ve come to see DEI as yet another front in a cultural war being waged against their values. When DEI is cast as “woke ideology” wrapped in a civil rights disguise, speaking out against its dismantling starts to feel like siding against your faith. That’s the bind — and the power — of persecution narratives in today’s political climate.

According to Barna Group and the St. Louis American, 68% of Black practicing Christians believe that racial inequality in housing and income is the result of ongoing discrimination. Only 32% of white practicing Christians say the same.

This difference isn’t just statistical — it’s theological, cultural, and experiential. Black Christians, who have long lived as both devout believers and marginalized citizens, tend to understand suffering and exclusion not as persecution to be avoided but as an experience that draws them closer to the story of Jesus. For white evangelicals, especially those used to being at the center of civic life, the loss of prominence can feel like an existential threat.

As noted in The Intercept article, this backlash against DEI has been weaponized by political leaders who’ve merged concerns about race, religion, and national identity into a single narrative of grievance:

"Trump and his allies have gone beyond criticisms of DEI in education or corporations to frame these programs as part of an anti-Christian, anti-American agenda. What began as a reaction to progressive racial justice movements has been recast as a spiritual battle."

This is what makes the persecution narrative so potent. It isn’t just about doctrine. It’s about perceived extinction. When religion, race, and politics are bundled together, the loss of cultural dominance feels like a moral emergency. It transforms policy debates into spiritual warfare. And it becomes easy to see any effort toward inclusion or equity as an attack on the gospel itself.

But here’s where a better, more faithful response might begin: by acknowledging that these fears are real — and then gently, honestly, putting them into context.

Yes, it can feel like persecution when something you’ve always known as "normal" is now challenged. Like when you say “Merry Christmas” at the store and someone responds with “Happy Holidays.” It’s a small moment, but it can feel like a loss for some — like the world you were raised in is slipping away. It’s disorienting to move from the center to the periphery, especially when your faith used to shape the culture around you. And yes, it’s tempting to see that shift as hostility, when in reality, it might just be others finally having space to be seen too.

But what if some of that discomfort is actually discipleship? What if losing cultural dominance is not a curse, but a calling?

Because the Bible doesn’t describe faith as something that guarantees power or popularity — even if some try to make it sound that way. In fact, it often warns that following Jesus leads us in the opposite direction: toward humility, sacrifice, and, yes, sometimes rejection.

How Can We Care for “The Least of These” When Some Christians Feel Like They’re One of Them?

It’s a fair and complicated question. When many Christians — especially white evangelicals — increasingly feel marginalized or pushed to the edges of culture, it can be hard to see beyond that experience. If you feel like you’ve become “the least of these,” the idea of serving others who are also struggling might feel overwhelming or even unfair. But Jesus doesn’t give us an exception clause. In Matthew 25, He calls us to care for the hungry, the sick, the imprisoned — not because we’re in power, but because we know what it means to be vulnerable. Maybe the challenge, then, is to let that feeling of marginalization deepen our empathy, not harden our hearts. If we truly believe we’re being sidelined, maybe that’s exactly the moment to turn toward others who’ve lived there far longer — and see them not as competitors in suffering, but companions in it.

“If the world hates you, keep in mind that it hated me first... If they persecuted me, they will persecute you also.” — John 15:18–20

“Indeed, all who desire to live a godly life in Christ Jesus will be persecuted.” — 2 Timothy 3:12

“Blessed are those who are persecuted because of righteousness… Rejoice and be glad, because great is your reward in heaven.” — Matthew 5:10–12

In other words, persecution isn’t evidence that something has gone wrong. It’s often a sign that something has gone right, and you have a tremendous opportunity to be a witness and show others how Jesus would respond.

The early church didn’t lobby the empire to protect them. They didn’t sue for their place at the table. They embraced the margins. And from those margins, they transformed the world. Maybe that’s the better invitation today: to stop fearing the loss of cultural dominance, and to start asking better questions about what we’ve been called to in the first place. Because fear can cloud our witness. It can cause us to see enemies where there are neighbors, to mistake equity for erasure, and to confuse cultural discomfort with divine punishment.

We live in a time when it's easy to become reactive — to retreat into grievance, to frame every challenge as an assault, and to long for the restoration of a world that gave many Christians a sense of inherited power. But if we are to be people of the truth, we have to ask hard questions. What exactly are we afraid of? Who taught us to fear it? And when does that fear stop being protective and start being corrosive?

When Christians conflate persecution with accountability, or faithfulness with power, we risk missing the very heart of the gospel. We risk turning our witness into a weapon. And the world sees it — especially those who have long lived on the outside of the religious mainstream. So maybe the invitation for us — especially for those of us who feel like outsiders in a changing world — is not to fight our way back to the center, but to rediscover the power of living faithfully on the margins.

That’s where Jesus lived. That’s where the early church found its strength. And maybe, just maybe, that’s where we’ll find ours too. The apostle Paul knew something about living in the margins. He wrote these words not from a place of comfort or cultural influence, but from a prison cell — under arrest for preaching the gospel, uncertain of what the future held:

“Do not be anxious about anything, but in every situation, by prayer and petition, with thanksgiving, present your requests to God. And the peace of God, which transcends all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus.” — Philippians 4:6–7

That’s not a call to deny what you feel — it’s a reminder that peace doesn’t require power. Like the sand rose, formed slowly in the harshest deserts, our faith can take shape even when we feel forgotten or pushed aside — proof that beauty and purpose can still rise from the margins.

To better understand why some Christians feel persecuted — and how that sense of loss has been politically harnessed — these books dive deep into the evolving relationship between Christianity and power in America. They unpack how figures like Donald Trump have become symbols of spiritual and cultural restoration for many, even as they challenge the core teachings of the faith.

(Currently banned by the Department of Defense) The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy and the Path to a Shared American Future

(Currently banned by the Department of Defense) White Evangelical Racism, Second Edition: The Politics of Morality in America

Baptizing America: How Mainline Protestants Helped Build Christian Nationalism

American Idolatry: How Christian Nationalism Betrays the Gospel and Threatens the Church

The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism